North Korea, so the scenario unfolds, gradually moves to a market economy under the grip of its one party rule. Its leaders keep tight control on the political and social repercussions of economic reforms, but over time the changes ineluctably lead to more wealth and a more open society.

"We South Koreans do not want abrupt change," said the South Korean foreign minister, Yoon Young-kwan, in a recent interview. "We are not ready to digest sudden change in the political situation in North Korea."

As the prospect of a negotiated end to the nuclear crisis with North Korea inches closer, South Koreans are now thinking seriously about the implications. There is the potential, they realize, for a terrible lesson in getting what you wish for.

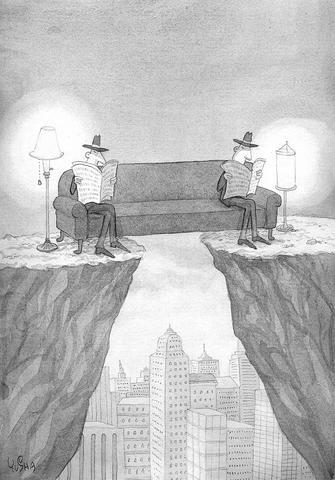

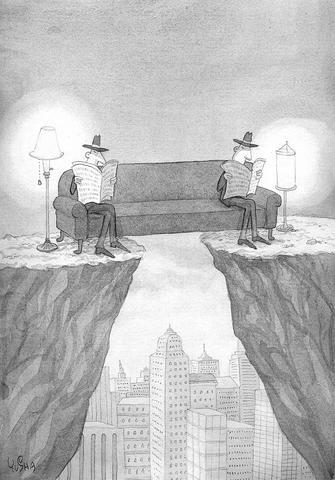

ILLUSTRATION MOUNTAIN PEOPLE

Abrupt change conjures up the nightmare image of millions of refugees from North Korea, a crashing economy, war. At the very least, the collapse of the demilitarized zone would be far messier to handle than the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The ideal of a gradual transformation to a market economy and a more open society -- played out in China, as well as in smaller countries in Asia and South America -- lies at the heart of South Korea's approach to North Korea, and is also the source of differences with Washington over how to resolve the crisis.

To the Bush administration, North Korea is part of the "axis of evil" and its leader, Kim Jong-il, an irredeemable "pygmy," as US President George W. Bush once said. To Seoul, though, North Korea stands where China did a couple of decades ago, and with the right nudge, here and there, Kim could metamorphose into the late Deng Xiaoping (

Asked whether Kim could assume a role similar to that of the Chinese reformer, Yoon said without hesitation, "I think so."

In an interview, Yoon cited the economic changes undertaken by North Korea since July last year. Government price controls have been lifted in an increasing number of markets in Pyongyang, the capital. Trade with South Korea has increased; South Korean companies are building cars, roads and railroads in North Korea and are planning to build factories in a special industrial zone in Kaesong, a town about 65km north of Seoul, just over the border.

Pointing out that Kaesong is an hour's drive from Seoul, Yoon again turned to the China model.

"We will be implementing a Hong Kong-Shenzhen model to the North Korean situation," he said. "Because Kaesong is so close to Seoul, if we can succeed in this project, the positive economic and political impact will be great.

"The key of our North Korean policy is helping North Korea adopt market mechanisms," he said. "That will help them rebuild their own economy, which will in turn bring about some positive domestic political impact and some positive impact in terms of North Korea's international behavior."

Contrast such talk with Washington's. Its recent strategy has been to apply mild economic pressures on North Korea and hint at more severe measures like UN sanctions, if negotiations collapse.

The other critical element of the Chinese model of development is that the move toward a market-based economy could not take place in a democracy. North Korea would live under an authoritarian government for an indefinite period.

"In the case of China, the reforms were made possible because Deng Xiaoping maintained strong leadership and stability politically," said Park Chan-bong, the deputy minister in the South Korean Unification Ministry.

"In the case of North Korea, Kim Jong-il is in full control of North Korea. If he decides to reform, then I think he can do it," he said.

This political model -- in addition to China, Yoon also spoke of Chile, Brazil or even South Korea as examples -- would allow North Korea to control the changes unleashed by markets.

But there are many doubts, not only in the US but also in South Korea, about whether North Korea is capable of following in China's footsteps.

The biggest misgiving centers on Kim Jong-il himself. The economic policies carried out in the last two years do not amount yet to evidence that he is fully committed to economic reforms. In fact, the so-called hawks here say that he has not shown any desire for real change, only survival. So Kim is compared less frequently to Deng than to Deng's predecessor, Mao Zedong (

"Many hope that he will become the next Deng Xiaoping," said Lee Geun, a professor of international relations at Seoul National University.

"But others argue that change in China happened only after the death of Mao, and that North Korea will not change until Kim Jong-il is eliminated," Lee said.

Others are unsure whether North Korea's leaders have the flexibility to accept or manage social and political shifts. Although Beijing cracked down on pro-democracy demonstrators in 1989, it was able to direct political changes by first limiting them to areas along China's coast.

Because of its small size, North Korea would find it difficult to restrict the effect of market reforms to a geographic area, said Ha Young-sun, a professor of international relations at Seoul National University.

"North Korea is very worried about the negative effects of capitalism," Ha said. "It would view them as a threat to the survival of the regime."

Even if North Korea were willing to accept these social transformations, experts say it lacks an independent way to finance its growth. China's economy was largely agricultural, and its leaders used agricultural reforms to expand its industrial sector. North Korea's economy is industrial, though with a highly educated work force, said Lim Won-hyuk, a specialist on the North Korean economy at the Korea Development Institute.

What is more, in its initial stage of economic reform, China relied heavily on overseas Chinese investors. North Korea would have to get large amounts of aid from the US, Japan and institutions like the World Bank and the IMF.

"For that, North Korea would need to improve its relations with the US," Lim said.

So that is another China parallel. North Korea needs better relations with the US, not only to obtain capital but to help would-be reformers outmaneuver hard-liners using a possible threat from America as leverage. China, after all, began opening up only after the former US president Richard Nixon's visit led to the normalization of relations. If only Nixon could open up China, maybe only Bush can open up North Korea.

Concerns that the US might abandon Taiwan are often overstated. While US President Donald Trump’s handling of Ukraine raised unease in Taiwan, it is crucial to recognize that Taiwan is not Ukraine. Under Trump, the US views Ukraine largely as a European problem, whereas the Indo-Pacific region remains its primary geopolitical focus. Taipei holds immense strategic value for Washington and is unlikely to be treated as a bargaining chip in US-China relations. Trump’s vision of “making America great again” would be directly undermined by any move to abandon Taiwan. Despite the rhetoric of “America First,” the Trump administration understands the necessity of

In an article published on this page on Tuesday, Kaohsiung-based journalist Julien Oeuillet wrote that “legions of people worldwide would care if a disaster occurred in South Korea or Japan, but the same people would not bat an eyelid if Taiwan disappeared.” That is quite a statement. We are constantly reading about the importance of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC), hailed in Taiwan as the nation’s “silicon shield” protecting it from hostile foreign forces such as the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), and so crucial to the global supply chain for semiconductors that its loss would cost the global economy US$1

US President Donald Trump’s challenge to domestic American economic-political priorities, and abroad to the global balance of power, are not a threat to the security of Taiwan. Trump’s success can go far to contain the real threat — the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) surge to hegemony — while offering expanded defensive opportunities for Taiwan. In a stunning affirmation of the CCP policy of “forceful reunification,” an obscene euphemism for the invasion of Taiwan and the destruction of its democracy, on March 13, 2024, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) used Chinese social media platforms to show the first-time linkage of three new

Sasha B. Chhabra’s column (“Michelle Yeoh should no longer be welcome,” March 26, page 8) lamented an Instagram post by renowned actress Michelle Yeoh (楊紫瓊) about her recent visit to “Taipei, China.” It is Chhabra’s opinion that, in response to parroting Beijing’s propaganda about the status of Taiwan, Yeoh should be banned from entering this nation and her films cut off from funding by government-backed agencies, as well as disqualified from competing in the Golden Horse Awards. She and other celebrities, he wrote, must be made to understand “that there are consequences for their actions if they become political pawns of