Every Tuesday morning during the Iraq war Washington's opinion-makers and journalists knew there was only one place to be: at the "black-coffee briefings" held at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), a fortress-like building on M and 17th streets, opposite the main offices of the National Geographic magazine.

Technically, AEI is a think tank. More than that, though, it is the headquarters of the intellectual movement known as neoconservatism. Its staff includes famous names such as Richard Perle, Irving Kristol and Newt Gingrich. The magazine Weekly Standard, the neocon bible, is published at the same address.

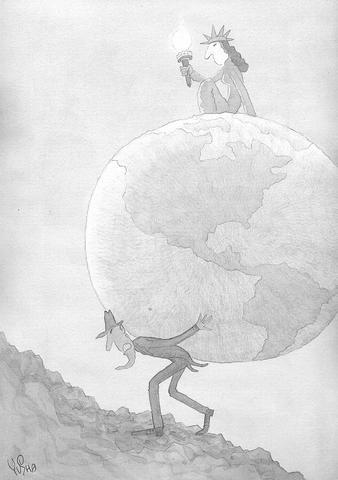

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

Black coffee was not strictly compulsory at the briefings -- adding milk was allowed -- but it did seem a particularly apt metaphor. The neocons felt they were delivering stern, sobering truths, wake-up calls with all the kick of a strong espresso: that liberating Iraq and making an awesome show of American power was vital for the US and the world, that democracy would spread through the region as dictators fell like dominoes.

Resistance would be minimal: the war could be fought, most argued, with the lean high-tech military championed by US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld.

But not with the UN and Europe, who did not have the stomach for the new era of muscular American power. But that was then; September in Washington finds the ultra-hawks in ferment. They confess to being taken aback by events in Iraq. Some are responding by arguing that the terrorist attacks on US troops there may actually be, counterintuitively, a good thing.

In interviews they expressed deep skepticism about US President George W. Bush's new overtures to the UN, accusing the White House of a lack of commitment -- and, most surprising of all, rounding on their former hero Rumsfeld. The distance between the president and the movement widely credited with persuading him to go to war in the first place has never seemed greater.

"All of us surely understand that, but for the president, we wouldn't be arguing about postwar Iraq -- we would still be arguing about what to do with Saddam," said Thomas Donnelly, an AEI scholar and senior fellow at the Project for the New American Century, the influential rightwing group whose founding signatories include Vice President Dick Cheney, Rumsfeld and his deputy, Paul Wolfowitz.

"But having got rid of the guy, we're now understanding that regime change is a much larger undertaking than we thought it was," he said.

"But this is a unique American responsibility, and passing the buck to the rest of the world, a good portion of which didn't agree with us in the first place, is not a great idea," he said.

There is still plenty of the old defiant optimism that prompted one AEI scholar, Danielle Pletka, to publish a paper in April, mid-war, bluntly entitled "Everything is Going Well."

Donnelly and his colleagues are emphatic that they still feel that way. But insufficient troops, he argues, mean "we're making it harder than it has to be."

The near-daily grim news of US casualties in Iraq has inspired some audacious responses -- most notably what has been labelled the "flypaper theory," pungently summarized by the conservative commentator Andrew Sullivan.

"Being based in Iraq helps us not only because of actual bases, but because the American presence diverts terrorist attention away from elsewhere," he argued on his website.

Even General Ricardo Sanchez, commander of the coalition's ground forces in Iraq, appeared to subscribe to this theory, conceding that Iraq was "a terrorist magnet" but adding: "This is exactly where we want to fight them."

Other neoconservatives disagree, however -- one of numerous ways in which their previous consensus seems to be fragmenting.

Some dissenters have seen the breach with the Pentagon coming since before the war. As an example, Rumsfeld was reported to have personally delayed the dispatch to Iraq of heavy artillery units based in Texas and Germany. Even to many hawks that seemed a foolhardy degree of commitment to the "revolution in military affairs," the doctrine that America will win the wars of the future with light, nimble forces using laser-guided missiles and precision bombs.

"Rumsfeld, in particular, has become a bit of a problem, because he's so committed to the revolution in military affairs that he doesn't like the idea of American ground troops patrolling, doing low-tech things," said William Kristol, editor of the Weekly Standard.

"But ... sometimes the world doesn't allow you to do everything with precision bombs. And I think we should be willing to do what it takes," he said.

In the interest both of American influence and the Iraqi people a much bigger commitment of US troops and money is essential, he argues. This is why the president's request for billions more in funds has spread some relief among the neocons. Some privately hint that they might prefer it if French and German opposition to Bush at the UN were to result in the defeat of US negotiators there.

One prominent pro-war voice has even said so publicly. "It would be a delightful irony if Jacques Chirac prevented President Bush from putting the wrong foot forward," Reuel Marc Gerecht of the AEI wrote recently in the Weekly Standard.

"[The administration has] been trying to do it on the cheap, and that's a mistake," Kristol said. "What's going to rectify that mistake is not the UN -- it's the US$87 billion, and a more urgent US commitment to getting it right, doing the reconstruction, and laying the conditions for the Iraqis taking over."

If the motives for urging an attack on Iraq in the first place seemed ever-changing, that might have been because, in the words of the liberal Washington commentator Joshua Micah Marshall, "it was the classic overdetermined question." Several of these thinkers' deeply held convictions, in other words, all pointed to the same conclusion.

They have a passionate belief in the benefits of US-style democracy. They want to stun potential enemies, both terrorists and "rogue states," into realising the scale of American force. They want to reduce US reliance on such allies as Saudi Arabia. And they want to reduce regional pressure on Israel.

All dictated the same thing: attacking Iraq. "There was a period where they had a way of winning all the arguments," said Marshall, who edits the widely read Web site TalkingPointsMemo.com.

"But now they're off their game plan, which is why you get this great diversity of arguments from them," he said.

A White House that appeared in tune with their thinking has proved to have other concerns: proving a point about military technology, in Rumsfeld's case, and, in the president's, winning the next election.

"There are people around the president who can see that, politically, this is a mess," Marshall said. "But the neocons see it all in grand-historical terms -- if it takes 100,000 soldiers, if it takes a draft, who cares? We gotta do it."

Their clarion call now is for the "Iraqification" of Iraq: an argument which brings the neoconservatives curiously close to the viewpoint put forward by the French and Germans at the UN.

"We need a game plan for a swift transfer to the Iraqis, because we haven't won until we have government by the Iraqis," Pletka said, although going to the UN, she added, "doesn't accelerate that, it decelerates it."

Pletka's version of the argument represents yet another emerging camp within the movement. She blamed the problems in Iraq on "a bizarre colonial attitude" on the part of US Secretary of State Colin Powell's state department and the British. But her comments underline a pervasive sense that the marriage of the neocons and the Rumsfeld wing of the Bush administration may be heading for the rocks.

Those with old-fashioned colonialist attitudes had influence over the governance of the country, Pletka said, "because they've got the bodies."

"And yet, for reasons utterly mysterious to me, the Pentagon refuses to send its people over there. They should be making sure they have a big role there, too. And they won't. And I have no idea why," she said.

Right stuff: the main players

By Julian Borger

Paul Wolfowitz

The most visible neocon in Washington, whose power transcends his modest title of deputy secretary of defense. Like almost all neocons, he is a former Democrat, combining a liberal sense of mission to spread democratic ideas with a traditional conservative readiness to use military force. But he is now at loggerheads with the "paleocons" about how long to stay in Iraq.

Richard Perle

Wolfowitz's mentor and veteran cold warrior from the Reagan administration, where he was known as the "prince of darkness." Like many a neocon, he began his career working for the hawkish Democratic senator Henry "Scoop" Jackson before defecting to the Republicans.

Forced to step down as chairman of the defense policy board in March after his many business connections raised questions of conflict of interest.

Douglas Feith

Another veteran Scoop Jackson Democrat, Feith stands out for his close ties with Israel's Likud party. His former law company had offices in Washington and Tel Aviv, and when he became undersecretary of defense for policy, overseeing the office of special plans and its search for damning "intelligence" on Iraq, he remained open to input from the Sharon government. Seen as the neocon most likely to fall if things turn from bad to worse in Iraq.

Elliott Abrams

The White House's chief adviser on the Middle East became notorious in the Reagan administration when he admitted misleading Congress about the Iran-contra scandal. Abrams, yet another Scoop Jackson graduate, backed Likud on the Middle East.

William Kristol

Offspring of the first neocon dynasty. Irving Kristol was a founder of the movement. His magazine, the Weekly Standard, is the main neocon sounding board in Washington.

Jan. 1 marks a decade since China repealed its one-child policy. Just 10 days before, Peng Peiyun (彭珮雲), who long oversaw the often-brutal enforcement of China’s family-planning rules, died at the age of 96, having never been held accountable for her actions. Obituaries praised Peng for being “reform-minded,” even though, in practice, she only perpetuated an utterly inhumane policy, whose consequences have barely begun to materialize. It was Vice Premier Chen Muhua (陳慕華) who first proposed the one-child policy in 1979, with the endorsement of China’s then-top leaders, Chen Yun (陳雲) and Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平), as a means of avoiding the

As the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) races toward its 2027 modernization goals, most analysts fixate on ship counts, missile ranges and artificial intelligence. Those metrics matter — but they obscure a deeper vulnerability. The true future of the PLA, and by extension Taiwan’s security, might hinge less on hardware than on whether the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) can preserve ideological loyalty inside its own armed forces. Iran’s 1979 revolution demonstrated how even a technologically advanced military can collapse when the social environment surrounding it shifts. That lesson has renewed relevance as fresh unrest shakes Iran today — and it should

The last foreign delegation Nicolas Maduro met before he went to bed Friday night (January 2) was led by China’s top Latin America diplomat. “I had a pleasant meeting with Qiu Xiaoqi (邱小琪), Special Envoy of President Xi Jinping (習近平),” Venezuela’s soon-to-be ex-president tweeted on Telegram, “and we reaffirmed our commitment to the strategic relationship that is progressing and strengthening in various areas for building a multipolar world of development and peace.” Judging by how minutely the Central Intelligence Agency was monitoring Maduro’s every move on Friday, President Trump himself was certainly aware of Maduro’s felicitations to his Chinese guest. Just

In the US’ National Security Strategy (NSS) report released last month, US President Donald Trump offered his interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine. The “Trump Corollary,” presented on page 15, is a distinctly aggressive rebranding of the more than 200-year-old foreign policy position. Beyond reasserting the sovereignty of the western hemisphere against foreign intervention, the document centers on energy and strategic assets, and attempts to redraw the map of the geopolitical landscape more broadly. It is clear that Trump no longer sees the western hemisphere as a peaceful backyard, but rather as the frontier of a new Cold War. In particular,