Mao Zedong (毛澤東) moved them in and now money is moving them out. The residents of Beijing's maze-like hutong neighborhoods were the heroes of the Chinese revolution, but they are now being evicted so that the property developers who hold sway in today's China can build high-rise residential blocks for a new generation of nouveaux riches.

For more than 100 years, the smoky-grey, walled courtyard of No 39 Dongsi 12th Lane has provided a refuge from the waves of imperial oppression, communist revolution and capitalist rapaciousness that have swept through China. Located in a hutong alley in the heart of Beijing's old city, the tiled-roof compound is just a two-minute walk from the choked-up streets and noisy construction sites that pollute the capital with dust and noise.

But you only have to duck through its narrow gateway to escape into a small oasis of pomegranate trees, gourd vines and neat rows of potted plants, where elderly men play Chinese chess, housewives hang their washing and schoolchildren bury their noses in homework.

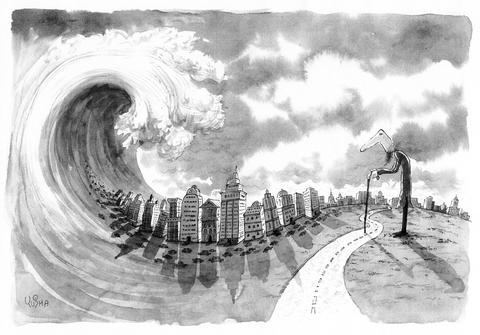

ILLUSTRATION: YU SHA

For eight centuries such quadrangle buildings, arranged in the tree-lined maze of hutongs, were the distinctive feature of life in Beijing -- once the world's most sophisticated city. But they are now being destroyed in their thousands as the Chinese capital undergoes one of the most dramatic transformations in the history of urban planning.

In a headlong rush to cash in on China's spectacular economic growth and to modernize Beijing before the 2008 Olympics, the old single-story neighborhoods are being flattened by developers keen to secure the high-value land on which they are situated. In their place come sleek high-rise buildings and apartment blocks almost indistinguishable from those found in cities around the world.

The destruction of an ancient heritage and a traditional way of life is belatedly raising alarm bells inside the Chinese government, but even with growing official support, conservationists are fighting a losing battle against the bulldozers and public indifference.

No 39 Dongsi 12th Lane is at the forefront of efforts to maintain the hutongs. This summer, the quadrangle -- once home to a Qing dynasty emperor's kung fu instructor and now home to 26 families -- was the first to be listed by the Beijing municipal government in its most ambitious conservation campaign yet.

Numerous stories have appeared in the Chinese media about the property, which is marked with a blue plaque declaring it to be a "protected courtyard".

Yet many fear it is too little, too late. According to the Beijing Weekender, a third of the 62km2 old city has already been demolished. Beijing says it will protect 200 homes, but more than 10,000 others are being knocked down every year, reducing the number of hutongs from their 1980s peak of 3,600 to fewer than 2,000 today.

"If they don't stop, Beijing as an historical city will cease to exist," warned the writer Hua Xinmin, a leading campaigner for the protection of the hutongs.

But there is little that opponents of development can do. Under Mao, the courtyards -- like all land -- were taken into state ownership. Their wealthy owners were replaced by the families of Chinese Communist Party cadres as a reward for their loyalty.

Now, however, they are at the mercy of a state that is obsessed with economic growth. With no ownership rights, residents, many of them retired, have little legal redress when their homes are listed for demolition by property speculators.

To developers, the hutong buildings are valueless.

"They only want the prime real estate they occupy," said Liu Xiaoshi, a senior architect and former member of Beijing's urban planning bureau.

"But the new properties are no substitute for the culture and spirit of the ones they replace," Liu said.

Despite such concerns, the priority of the municipal authorities is modernization, not conservation. Beijing plans to spend US$22 billion on beautifying the city in time for the 2008 Olympics. The construction boom has attracted architects from across the globe to work on such lavish projects as the US$300 million bubble-shaped opera house designed by Frenchman Paul Andreu which is being built opposite the Forbidden City; and what will be the city's tallest building, a US$600 million headquarters for the state broadcaster designed by two Dutch architects, Ole Scheeren and Rem Koolhaas. Elsewhere the transformation is more prosaic: narrow hutong streets knocked down for wide boulevards of office blocks and shopping malls filled with Starbucks, McDonald's and KFC outlets.

As more new buildings go up, a growing number of courtyard residents are being moved into high-rise apartment blocks in the suburbs. Many go willingly, glad to swap a cramped life of foul communal toilets and smoky coal stoves for spacious flats with private bathrooms and central heating. Others attempt opposition, but their petitions and court orders are ignored by the powerful developers.

Residents appear fatalistic.

"There's not much we can do if they want to redevelop our home," said Li Ruiling, whose home for 38 years on Dongsi 12th Lane backs on to a construction site for a new subway station.

"And preservation is no solution, because we'd have to move out while they fix the place up and then it would be too expensive to move back in," Li said.

Though the central government is belatedly recognizing that their homes and their way of life are cultural treasures, it is no longer able to rein in the runaway development it has unleashed. Many observers fear that No 39 Dongsi 12th Lane may end up among the last of the hutongs.

"The central government says it has stopped the destruction of the courtyards, but the reality is that on the ground they are still knocking them down," said Edward Lanfranco, the author of a book on Beijing.

"Small pockets of courtyard areas may survive, but the future for old Beijing is likely to be a Disneyland area for tourists. Meanwhile an 800-year-old way of life will have disappeared," he said.

President William Lai (賴清德) attended a dinner held by the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC) when representatives from the group visited Taiwan in October. In a speech at the event, Lai highlighted similarities in the geopolitical challenges faced by Israel and Taiwan, saying that the two countries “stand on the front line against authoritarianism.” Lai noted how Taiwan had “immediately condemned” the Oct. 7, 2023, attack on Israel by Hamas and had provided humanitarian aid. Lai was heavily criticized from some quarters for standing with AIPAC and Israel. On Nov. 4, the Taipei Times published an opinion article (“Speak out on the

The image was oddly quiet. No speeches, no flags, no dramatic announcements — just a Chinese cargo ship cutting through arctic ice and arriving in Britain in October. The Istanbul Bridge completed a journey that once existed only in theory, shaving weeks off traditional shipping routes. On paper, it was a story about efficiency. In strategic terms, it was about timing. Much like politics, arriving early matters. Especially when the route, the rules and the traffic are still undefined. For years, global politics has trained us to watch the loud moments: warships in the Taiwan Strait, sanctions announced at news conferences, leaders trading

Eighty-seven percent of Taiwan’s energy supply this year came from burning fossil fuels, with more than 47 percent of that from gas-fired power generation. The figures attracted international attention since they were in October published in a Reuters report, which highlighted the fragility and structural challenges of Taiwan’s energy sector, accumulated through long-standing policy choices. The nation’s overreliance on natural gas is proving unstable and inadequate. The rising use of natural gas does not project an image of a Taiwan committed to a green energy transition; rather, it seems that Taiwan is attempting to patch up structural gaps in lieu of

News about expanding security cooperation between Israel and Taiwan, including the visits of Deputy Minister of National Defense Po Horng-huei (柏鴻輝) in September and Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Francois Wu (吳志中) this month, as well as growing ties in areas such as missile defense and cybersecurity, should not be viewed as isolated events. The emphasis on missile defense, including Taiwan’s newly introduced T-Dome project, is simply the most visible sign of a deeper trend that has been taking shape quietly over the past two to three years. Taipei is seeking to expand security and defense cooperation with Israel, something officials