Ari Eisenberg was born in 1971 with blisters on his hands. The skin on his feet had fallen off because he had kicked in the womb. He had to be fed by a nasal tube because blisters in his mouth made breast-feeding impossible.

Afflicted with a rare genetic skin disease, Ari faced a short, painful life. "I visualized his future prospects and they looked very grim," recalled his father, Dr Mark Eisenberg. "I was determined not to accept that."

Eisenberg, a general practitioner with no particular expertise in research or dermatology, set out on a quest to save his son. One thing he developed was an artificial skin. Now, 30 years later, Ortec International, a company he co-founded, hopes to market that skin to treat burn victims.

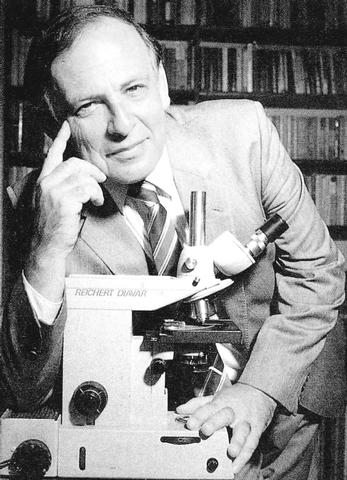

PHOTO: NY TIMES

Not all biotechnology companies are started by scientists eager to advance medicine or make money. Some are started by ordinary people -- a computer salesman, a shrimp processor, meat distributors and lawyers, among others -- hoping to cure a loved one. Their stories echo the movie Lorenzo's Oil, but with a corporate twist.

Nor are scientists already working at biotechnology companies immune from making a business of their personal crusades. Dr Julia Levy was chief scientist at a Canadian biotech startup working on a cancer drug when her mother was diagnosed with age-related macular degeneration, an eye condition that causes blindness.

"I had never heard of the disease," Levy recalled. But after hearing scientists discuss it at conferences, she realized that her company's drug might work for the eye condition. Today, Levy is president of the company, QLT Inc, which sells the only drug for macular degeneration.

Many people with sick relatives will try to collect money, start a foundation, lobby Congress, harangue scientists and take other steps to spur research on that disease. But some say nonprofit research is not enough to bring a drug to market. They start companies to try to get the job done.

At first, Martine A. Rothblatt, a Washington attorney and satellite entrepreneur, started a foundation to seek a cure for pulmonary hypertension, a potentially fatal condition that afflicts her youngest daughter. Then Rothblatt went on to start United Therapeutics, which is now seeking Food and Drug Administration approval of a drug for the disease.

"If you want to cure something you have to do it yourself," she said.

In perhaps no other industry could such a personal stake be so crucial to the start of a business. But having an executive desperate to save a relative can be a double-edged sword for investors. It motivates the executive but can divert corporate attention to, say, a rare disease offering only limited sales for its products. And there can be many emotional distractions.

"What looks like greater motivation could be a shell for what later ends up breaking that person apart," said David R. Cox, a Stanford University geneticist and pediatrician who often deals with parents of children with rare genetic diseases. Many such parents, he said, plunge into work on a cure as a way to "avoid dealing with the difficult reality" facing their children.

That was an issue raised in Lorenzo's Oil, the 1992 movie based on a true story of parents who developed a drug to treat their son's rare neurological disease. But not all such stories end so hopefully.

Floyd Nichols, a computer entrepreneur with a hereditary disease that almost invariably leads to colon cancer, started Cell Pathways to develop a drug that promised to keep him alive. But he died in 1996, before the drug was ready.

Even after Cell Pathways completed its research, the FDA decided last September not to approve the drug as a treatment for that disease, familial adenomatous polyposis.

Cell Pathways, based in Horsham, Pennsylvania., is still using the drug experimentally to treat Nichols' son, Eric, 13, who inherited the disease. And it is hopeful the drug will some day be approved as a treatment for several types of cancer. But its stock has lost two-thirds of its value.

That illustrates the potential drawback of making a business of a personal crusade. As compelling as their stories may be, companies based on a founder's search for a cure have to make a case to investors on business terms. "Why should people invest in Martine's quest to cure her daughter?" Rothblatt said. "I have to build the company to be the Amgen of the East."

So far, none of these family-founded startups has come close to the success of that California biotech giant. Indeed, the corporate missions of many of them have diverged from the personal quests that led to their creation, so if the company succeeds, it will be others, not the founders' loved ones, who will benefit.

That is the case with QLT. Levy's mother lost her vision and died from old age in 1996, never getting to try the eye drug. "The only thing I can give her," Levy said, "is a legacy."

Brain Tumors: A Quest to Restore Balance

A play date changed the career of Richard Garr, a lawyer and real estate developer near Washington.

Garr's son, Matt, had had a brain tumor removed when he was 4, but the benign growth had permanently impaired the boy's sense of balance. A few years later, Garr took Matt to play at the home of a classmate. Garr recalled that when he explained to the classmate's father not to be alarmed about Matt's balance problems, the man replied, "Oh, some day we'll be able to fix that."

The man, Karl K. Johe, was a scientist at the National Institutes of Health working on neural stem cells. Johe said such cells, which can be grown in test tubes, might one day be implanted into the brain to rewire broken circuits. "Did I want to believe him? Sure," recalled Garr. "Did I want someone to come along and say they can cure brain cancer? Sure."

The two men formed a company, NeuralStem Biopharmaceuticals, in 1996, with Garr as chief executive, Johe as chief scientist and US$1.5 million raised from Garr's friends and business associates. The company, which is privately owned, now has 40 employees and is based at the University of Maryland.

There never really was much chance that the company's work would help Matt Garr. It will be years before NeuralStem will even attempt to transplant cells into people. And the first targets will probably be Parkinson's and Lou Gehrig's diseases, which are considered easier to treat than brain tumors. "The stem cell technology was too far away to be beneficial to Matt," Johe said. "That's still the case. I'm sure Richard knew that, too."

In any case, Matt, now 14, leads a fairly normal life, except that he has trouble playing certain sports. But his tumor recently grew again and he underwent radiation therapy.

Garr said he realized that nothing would be done for brain tumors unless the company tackled other areas first. "We're not going to get to there until we have a huge company with huge resources," he said. So the emphasis is on succeeding as a business. Still, he said, his personal experience has imparted a sense of urgency to his work.

Hanging on the wall above his desk are reprints of newspaper articles about a local girl who underwent experimental gene therapy to treat a brain tumor. It failed and she died. "Every day is the last day for somebody, someplace," Garr said.

When her daughter, Jenesis, was diagnosed with primary pulmonary hypertension, a potentially fatal obstruction of the blood vessels feeding the lungs, Martine Rothblatt did not think there was much she could do except rely on doctors. That is, until 8-year-old Jenesis, having lived with the disease for two years, asked her parents one day why they themselves couldn't work on a cure.

"It was like an epiphany," Rothblatt said. "Somehow, for the rest of the day, I couldn't get that out of my mind."

Rothblatt was not one to shirk a challenge. She had helped start and run several satellite-communications companies like PanAmSat.

Within a month she had sold her satellite interests and started the nonprofit PPH Cure Foundation. But in 1995, a doctor treating Jenesis told Rothblatt of an experimental drug that Burroughs Wellcome had abandoned because the market was perceived as too small.

Rothblatt contacted the scientist who had led the project, James Crow, and pleaded to meet with him, even though he had left the company after it was acquired by Glaxo. "I said, `Dr Crow, my daughter's life is at stake,'" she recalled.

Rothblatt flew Crow from his home in North Carolina to Washington the next day, and within hours they agreed to form United Therapeutics. Rothblatt, the chief executive, promised to pay the salaries of Crow and his associates from her own pocket at first.

The new company expected to have a difficult time getting rights to the drug from Glaxo. But fate intervened. The sister of a top Glaxo researcher had recently been diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension.

The next challenge was to raise money. While the number of Americans and Europeans with primary pulmonary hypertension is small, about 5,000, as many as 100,000 people have a related disease called secondary pulmonary hypertension. United Therapeutics lumped the two conditions together and argued that sales of a successful drug could eventually exceed US$2 billion.

Investors bought the argument -- and United Therapeutics stock, which went on sale in June 1999. Many investors were impressed by the personal nature of Rothblatt's mission, said Robert J. Toth Jr., who was an analyst at Vector Securities, one manager of the stock offering.

But United Therapeutics is no longer purely a labor of love. Rothblatt earns US$250,000 a year, and her stake in the company is worth more than US$20 million. The company bought its headquarters building in Silver Spring, Maryland, from her for US$581,000 and paid US$555,000 last year to a law firm in which she is a partner.

And Jenesis, now 16, is one of the minority of patients whose disease can be kept in check by existing heart medications. So at least for now she does not need United Therapeutics' drug.

The drug, Remodulin, did not work as well as expected in clinical trials, and the FDA, which was supposed to decide by April whether to approve the drug for sale, postponed its verdict until July. The company's stock, which soared as high as US$132 last July, has sunk to about US$14.

Rothblatt says she is confident Remodulin will be approved. And, she added, the company has other projects as well, many related to pulmonary hypertension.

Dr Robyn J. Barst of Columbia Presbyterian Medical Center, who first told Rothblatt about the Burroughs drug and is now on United's scientific advisory board, is also confident. "I've never met anyone as driven as Martine," she said.

Search for a cure, then a memorial

When Mark Eisenberg, who lives in Australia, determined to help his son 30 years ago, starting a company was the furthest thing from his mind.

Ari suffered from epidermolysis bullosa (EB), a rare disease in which the skin easily blisters. Eisenberg traveled the world to attend conferences and to speak to experts on the disease. He began research on his own. He helped set up a specialized clinic at a hospital in Sydney. It was struggle to keep Ari alive.

One complication of Ari's illness is that scar tissue can cause victims' hands to contract into a fist, then fuse into a useless stump. Ari needed skin grafts to open his hands -- no easy task since much of his body was covered with blisters.

So Eisenberg, taking a cue from an American scientist, tried to grow an artificial skin in a test tube, starting with foreskins from circumcisions. As an observant Jew who is certified to perform ritual circumcisions, Eisenberg even obtained some of the foreskins himself.

In the late '80s, Ari and some other Australian children with EB were treated with the artificial skin, which acts as a living bandage to promote growth of the patients' own skin. Eisenberg wanted to make the skin more widely available, but could not raise money for a skin bank.

In 1990, while in New York for a medical conference, he explained his problem to Steven Katz, a distant relative who taught finance at City University and also ran a meat distribution business. Katz advised Dr Eisenberg to start a company, and to emphasize the potential of the test-tube skin for bigger markets like treating burns and ulcers.

Ortec International was formed in New York in 1991 with Katz as chief executive and Ron Lipstein, his partner in the meat business and the owner of a mail order doll-parts catalog, as chief financial officer. Eisenberg became chief scientist and a director, staying in Sydney. "We thought it would be three years and US$5 million to be finished with the project," Katz recalled.

It has taken 10 years and US$50 million so far. But in February, the Food and Drug Administration approved the company's Composite Cultured Skin for use in hand surgery on patients with Ari Eisenberg's form of EB. Under a special humanitarian rule for rare diseases, only limited clinical trials were required.

The approval means little to the business because there are perhaps only a few hundred people in the US with that form of EB and because another artificial skin, made by Organogenesis Inc of Canton, Massachusetts, is already on the market.

In July, an FDA advisory committee will consider Ortec's application to use the skin on burn victims, a far bigger market. The company is also testing the skin as a treatment for leg ulcers and diabetic ulcers.

Still, the approval for EB marked a milestone in Eisenberg's 30-year odyssey. But the joy for him was muted: Ari was seriously ill.

Despite frequent operations, Ari had achieved a semblance of a normal life. After working for Ortec as a computer programmer while earning a college degree, he took a job for the Australian operations of Toshiba. He moved out of his parents' home into an apartment with his brother. Ari, who as a baby couldn't crawl without the skin coming off his knees, even took up skiing.

But when he was 25, Ari's kidneys failed, possibly as a result of his disease, and his health deteriorated. He died in April, two months after the FDA approved his father's artificial skin for use on his disease.

"It's almost like his life's mission was done," Katz said.

Eisenberg said he wanted to continue working with Ortec, to see that the skin is widely used. That, he said, would be "a fitting memorial" for his son.

US President Donald Trump yesterday announced sweeping "reciprocal tariffs" on US trading partners, including a 32 percent tax on goods from Taiwan that is set to take effect on Wednesday. At a Rose Garden event, Trump declared a 10 percent baseline tax on imports from all countries, with the White House saying it would take effect on Saturday. Countries with larger trade surpluses with the US would face higher duties beginning on Wednesday, including Taiwan (32 percent), China (34 percent), Japan (24 percent), South Korea (25 percent), Vietnam (46 percent) and Thailand (36 percent). Canada and Mexico, the two largest US trading

AIR SUPPORT: The Ministry of National Defense thanked the US for the delivery, adding that it was an indicator of the White House’s commitment to the Taiwan Relations Act Deputy Minister of National Defense Po Horng-huei (柏鴻輝) and Representative to the US Alexander Yui on Friday attended a delivery ceremony for the first of Taiwan’s long-awaited 66 F-16C/D Block 70 jets at a Lockheed Martin Corp factory in Greenville, South Carolina. “We are so proud to be the global home of the F-16 and to support Taiwan’s air defense capabilities,” US Representative William Timmons wrote on X, alongside a photograph of Taiwanese and US officials at the event. The F-16C/D Block 70 jets Taiwan ordered have the same capabilities as aircraft that had been upgraded to F-16Vs. The batch of Lockheed Martin

China's military today said it began joint army, navy and rocket force exercises around Taiwan to "serve as a stern warning and powerful deterrent against Taiwanese independence," calling President William Lai (賴清德) a "parasite." The exercises come after Lai called Beijing a "foreign hostile force" last month. More than 10 Chinese military ships approached close to Taiwan's 24 nautical mile (44.4km) contiguous zone this morning and Taiwan sent its own warships to respond, two senior Taiwanese officials said. Taiwan has not yet detected any live fire by the Chinese military so far, one of the officials said. The drills took place after US Secretary

THUGGISH BEHAVIOR: Encouraging people to report independence supporters is another intimidation tactic that threatens cross-strait peace, the state department said China setting up an online system for reporting “Taiwanese independence” advocates is an “irresponsible and reprehensible” act, a US government spokesperson said on Friday. “China’s call for private individuals to report on alleged ‘persecution or suppression’ by supposed ‘Taiwan independence henchmen and accomplices’ is irresponsible and reprehensible,” an unnamed US Department of State spokesperson told the Central News Agency in an e-mail. The move is part of Beijing’s “intimidation campaign” against Taiwan and its supporters, and is “threatening free speech around the world, destabilizing the Indo-Pacific region, and deliberately eroding the cross-strait status quo,” the spokesperson said. The Chinese Communist Party’s “threats