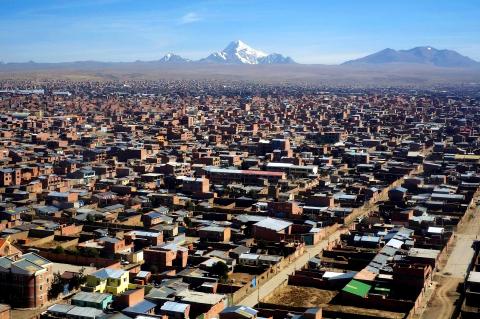

A chaotic sprawl high in the Andes, the Bolivian city of El Alto has a fearsome reputation for altitude sickness, poverty and violent uprisings that topple governments.

Yet years of economic growth and relative stability are changing attitudes as well as fortunes in one of Latin America’s poorest nations. Entrepreneurs are even waking up to El Alto’s potential.

Its first supermarkets, shopping centers and cinemas are planned — multimillion-dollar private sector investments that would have been unthinkable almost anywhere in Bolivia a decade ago.

Photo: Reuters

Banks and pizza delivery stores have set up shop in the city’s traffic-choked streets and its bare brick buildings are climbing higher into the thin air as local commerce thrives 4,050m above sea level.

“People hardly bought anything in the past. With this government there’s business,” said Alicia Villalba, 33, selling Brazilian-made aluminum pans at a twice-weekly market where about US$2 million changes hands every day.

Seven years since they helped elect leftist coca farmer Bolivian President Evo Moraless — the first president of indigenous descent — there are subtle signs of change among El Alto’s mainly Aymara Indian population too.

“El Alto was always where conflicts kicked off. Why? Because people had nothing to lose. That’s not the case today,” said Alejandro Yaffar, a prominent businessman who owns a new fast food court in El Alto.

However, much remains to be done. Heaps of garbage and packs of stray dogs blight the bleak urban landscape. Water and drainage are inadequate, and local businesses complain about rising crime and scant policing.

Public infrastructure projects have struggled to meet the fast-growing city’s needs or the expectations of residents and some are disappointed with Morales and the pace of change.

“Here in El Alto we all voted for him, myself included,” said Nora Villeros, 65, as she sat in front of her busy store. “He promised us miracles, but the first couple of years went by and then he forgot about us.”

El Alto is not the only place that is changing in Bolivia, a landlocked country of about 10 million that sits on South America’s second-biggest natural gas reserves and rich deposits of silver, tin, zinc and other metals.

In the capital, La Paz, which lies in a crater-like valley below El Alto, low unemployment and affordable credit are fueling a construction boom and consumers feel unusually well off.

“There’s more work and more money around. I think people are living better than they were six years ago,” said Marco Arkaza, 33, a bank employee.

After seven years of economic growth averaging 4.7 percent a year, Bolivia joined the World Bank’s list of lower middle-income countries in 2010. The ranking allows more credit access.

Government officials say up to 1 million Bolivians have entered middle-class ranks under Morales. They credit policies such as welfare payments for school children and pensioners for lifting almost 1 million more out of extreme poverty.

In 2006, 38 percent of Bolivians lived in extreme poverty, data from the state-run INE national statistics shows. That has fallen to about 25 percent, though nearly half of Bolivians are still poor, according to the UN.

Some sectors have done better than others. Critics say a disproportionate amount of public money has been poured into the Chapare region that is home to much of Bolivia’s illegal coca crops and a Morales stronghold.

Mining cooperatives have won political concessions from Morales and a few have grown rich due to soaring global metals prices.

In mining cities like Oruro and Potosi, newspapers carry stories of miners-turned-millionaires, luring fortune seekers from other parts of the country.

While most of the cooperative miners scrape a living working in dangerous and precarious conditions, a few have become wealthy enough to buy expensive cars and invest in real estate.

“This amazing mining boom has helped develop markets in places no one ever would have imagined,” said Christian Eduardo, president of the CADECO construction industry chamber.

Construction activity has been growing at an average of about 10 percent per year since 2007, forcing the over-stretched local cement industry to meet demand with Peruvian imports.

To the surprise of his detractors, Morales — an ally of Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez who shares his penchant for fiery leftist rhetoric — has proved a fiscal conservative. Bolivia is expected to register its seventh straight annual fiscal surplus this year.

Morales, 53, has nationalized areas of the economy from the vital natural gas industry to telecommunications companies and tin smelters, but he has also let the central bank’s foreign reserves swell to record levels and warded off the scourge of high inflation that battered Bolivia in the 1980s.

The economy is expected to grow more quickly than many of its wealthier neighbors this year and should maintain a healthy 5 percent expansion next year, the latest IMF estimates show.

“Bolivia is no longer a country with a weak economy,” Bolivian Minister of Economics Luis Arce said last month after the nation sold its first global bonds in almost a century.

Most analysts said the interest rate of less than 5 percent was low considering Morales’ record of nationalizing companies, often without prior notice or compensation, and it has proved an unlikely public relations success for him.

“The interesting thing is that Bolivia sold the bonds at half the rate paid by Venezuela. That’s an important message to the world,” said Horst Grebe, director of La Paz-based research agency Prisma. “The problem is that Bolivia’s biggest growth is in its macroeconomic numbers. What we’re not seeing is a transformation of the productive economy that is sustainable in the long term.”

Bolivia remains dependent on exports of non-renewable raw materials. Natural gas and metals made up 87 percent of last year’s record US$9.1 billion export earnings, the Bolivian Foreign Trade Institute’s Gary Rodriguez said.

Yet as Wall Street economists laud Morales’ macroeconomic policies as prudent, critics at home say he betrayed supporters by watering down policy pledges and pandering to big business.

“Since the Spanish arrived 500 years ago we’d never had an Indian president. It was the people’s dream and we thought things would be different, but six years on, he’s dishonored us,” said long-time indigenous activist Felipe Quispe, known as El Mallku, the “Condor” or “authority” in Aymara.

With six years and 10 months in the job, Morales has held Bolivia’s presidency for the longest unbroken period of any elected leader. An opinion poll conducted last month by Ipsos Bolivia put his approval rating at 53 percent in urban areas and 69 percent in the countryside.

Yet despite his continuing domination of the political scene, Morales has lost his initial aura of invincibility since some allies turned against him over an Amazon highway plan and a fuel price hike two years ago.

Government critics from the left and the right would like to see strong challengers emerge in time for a 2014 presidential election in which Morales has hinted he may seek a third term.

In El Alto, several large state infrastructure projects, such as a US$234 million cable car system, should be ready in time for the election, but are unlikely to satisfy growing expectations.

“There’s been a lot of investment in the city, but it hasn’t been enough yet,” said Javier Ajno, president of the powerful FEJUVE neighborhood federation.

FEJUVE was a protagonist in the so-called Gas War that led to the ouster of former Bolivian president Gonzalo Sanchez de Lozada in 2003.

Ajno said El Alto’s rebellious spirit was still very much alive, but that for now there is broad support for Morales.

“El Alto has been the cradle of this process of change ... we’ve carried an Indian to the presidency and people still believe in this process,” he said.

Semiconductor shares in China surged yesterday after Reuters reported the US had ordered chipmaking giant Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電) to halt shipments of advanced chips to Chinese customers, which investors believe could accelerate Beijing’s self-reliance efforts. TSMC yesterday started to suspend shipments of certain sophisticated chips to some Chinese clients after receiving a letter from the US Department of Commerce imposing export restrictions on those products, Reuters reported on Sunday, citing an unnamed source. The US imposed export restrictions on TSMC’s 7-nanometer or more advanced designs, Reuters reported. Investors figured that would encourage authorities to support China’s industry and bought shares

TECH WAR CONTINUES: The suspension of TSMC AI chips and GPUs would be a heavy blow to China’s chip designers and would affect its competitive edge Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電), the world’s biggest contract chipmaker, is reportedly to halt supply of artificial intelligence (AI) chips and graphics processing units (GPUs) made on 7-nanometer or more advanced process technologies from next week in order to comply with US Department of Commerce rules. TSMC has sent e-mails to its Chinese AI customers, informing them about the suspension starting on Monday, Chinese online news outlet Ijiwei.com (愛集微) reported yesterday. The US Department of Commerce has not formally unveiled further semiconductor measures against China yet. “TSMC does not comment on market rumors. TSMC is a law-abiding company and we are

FLEXIBLE: Taiwan can develop its own ground station equipment, and has highly competitive manufacturers and suppliers with diversified production, the MOEA said The Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA) yesterday disputed reports that suppliers to US-based Space Exploration Technologies Corp (SpaceX) had been asked to move production out of Taiwan. Reuters had reported on Tuesday last week that Elon Musk-owned SpaceX had asked their manufacturers to produce outside of Taiwan given geopolitical risks and that at least one Taiwanese supplier had been pushed to relocate production to Vietnam. SpaceX’s requests place a renewed focus on the contentious relationship Musk has had with Taiwan, especially after he said last year that Taiwan is an “integral part” of China, sparking sharp criticism from Taiwanese authorities. The ministry said

US President Joe Biden’s administration is racing to complete CHIPS and Science Act agreements with companies such as Intel Corp and Samsung Electronics Co, aiming to shore up one of its signature initiatives before US president-elect Donald Trump enters the White House. The US Department of Commerce has allocated more than 90 percent of the US$39 billion in grants under the act, a landmark law enacted in 2022 designed to rebuild the domestic chip industry. However, the agency has only announced one binding agreement so far. The next two months would prove critical for more than 20 companies still in the process