Business consultant Adrian Mutton says it takes courage for a foreign corporation to make a big-ticket investment in India given the uncertainties thrown up by capricious twists in government policy.

Companies have long griped about India’s byzantine rules and suffocating bureaucracy, but recent policy flip-flops have further soured the investor mood.

“You have got to be a pretty brave CEO to gamble on a major investment decision in India, especially if you think that decision may be overturned,” said Mutton, who heads India-based Sannam S4, a consultancy which helps firms enter India.

The latest, and for many investors most egregious government measure, was announced in last month’s budget which included provisions allowing India to tax foreign takeovers retroactively to 1962.

The measure seeks to override an Indian Supreme Court judgement in January that rejected a US$2.2-billion tax bill slapped on British phone giant Vodafone over its 2007 purchase of a local operator.

“The Indian government is perhaps hoping the country’s economic growth potential will retain companies like Vodafone,” said Deepak Lalwani, chief of India-focused investment consultancy Lalcap.

“However, fresh capital will be fearful of the business and investment climate and will be hesitant to come,” he said, cautioning that poor investor sentiment “might dramatically slow future foreign capital.”

Already, gross foreign direct investment in India has fallen by a quarter to US$20.3 billion in the fiscal year that ended last month, down from US$27.1 billion the previous year, according to official figures.

In a letter to India Prime Minister Manmohan Singh earlier this month, seven global business groups, including the Confederation of British Industry and the US Business Roundtable, warned of a “widespread reconsideration of the costs and benefits of investing in India.”

The investment slowdown comes as India urgently needs foreign funds to upgrade its dilapidated airports, roads, ports and other infrastructure in order to ease bottlenecks and spur growth.

Economic expansion for the last fiscal year is estimated to have been about 6.9 percent, the -second-slowest rate in a decade.

The retroactive change to India’s tax code was only the latest piece of news to dismay foreign investors, already preoccupied by policy paralysis on reforms to liberalize the economy and corruption.

The investment plans of Norwegian telecom giant Telenor and other foreign firms who had jumped into the world’s second-largest mobile market were left in tatters earlier this year when the Supreme Court of India canceled their licenses.

The court’s move stemmed from a scandal in which the government had issued mobile licenses in 2008 at throw-away prices, costing the public treasury up to US$39 billion, in what is believed to be India’s biggest graft case.

The license cancelation “was a shock for the foreign operators, especially as this was a ruling on a government policy decision,” said Kamlesh Bhatia, India research director at global consultancy Gartner.

In December last year, in a major U-turn, the government reversed a decision to allow foreign supermarkets into India after a key ruling coalition ally said the move could hurt millions of small shopkeepers in the country.

“The reform process has really just fallen apart,” Indian Council on Global Relations head Manjeet Kripalani said.

Further discouragement has come from a slew of stalled projects, including South Korean steelmaker POSCO’s plans to build a US$12-billion steel mill — first announced in 2005 and trumpeted as India’s biggest foreign investment deal.

Late last month, an Indian tribunal suspended environmental clearance for the plant, keeping the project in limbo.

However, many global companies have little choice but to enter the increasingly affluent country of 1.2 billion people if they want to boost revenues in light of the slowdown in developed economies, Mutton said.

“You cannot afford not to be in India as a marketplace when you look at the huge population,” says Mutton, whose India advisory business has tripled in size over the past few years.

“In boardrooms around the world, people are saying if we are going to deliver growth, where do we go? India inevitably comes up. They may know it will be a pain in the backside, but they have to make the best of the situation,” he said.

Hon Hai Precision Industry Co (鴻海精密) yesterday said that its research institute has launched its first advanced artificial intelligence (AI) large language model (LLM) using traditional Chinese, with technology assistance from Nvidia Corp. Hon Hai, also known as Foxconn Technology Group (富士康科技集團), said the LLM, FoxBrain, is expected to improve its data analysis capabilities for smart manufacturing, and electric vehicle and smart city development. An LLM is a type of AI trained on vast amounts of text data and uses deep learning techniques, particularly neural networks, to process and generate language. They are essential for building and improving AI-powered servers. Nvidia provided assistance

DOMESTIC SUPPLY: The probe comes as Donald Trump has called for the repeal of the US$52.7 billion CHIPS and Science Act, which the US Congress passed in 2022 The Office of the US Trade Representative is to hold a hearing tomorrow into older Chinese-made “legacy” semiconductors that could heap more US tariffs on chips from China that power everyday goods from cars to washing machines to telecoms equipment. The probe, which began during former US president Joe Biden’s tenure in December last year, aims to protect US and other semiconductor producers from China’s massive state-driven buildup of domestic chip supply. A 50 percent US tariff on Chinese semiconductors began on Jan. 1. Legacy chips use older manufacturing processes introduced more than a decade ago and are often far simpler than

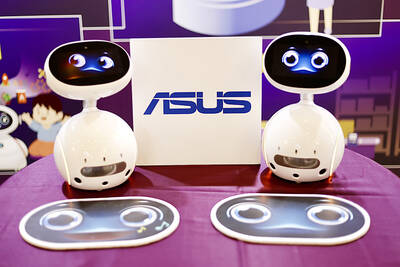

STILL HOPEFUL: Delayed payment of NT$5.35 billion from an Indian server client sent its earnings plunging last year, but the firm expects a gradual pickup ahead Asustek Computer Inc (華碩), the world’s No. 5 PC vendor, yesterday reported an 87 percent slump in net profit for last year, dragged by a massive overdue payment from an Indian cloud service provider. The Indian customer has delayed payment totaling NT$5.35 billion (US$162.7 million), Asustek chief financial officer Nick Wu (吳長榮) told an online earnings conference. Asustek shipped servers to India between April and June last year. The customer told Asustek that it is launching multiple fundraising projects and expected to repay the debt in the short term, Wu said. The Indian customer accounted for less than 10 percent to Asustek’s

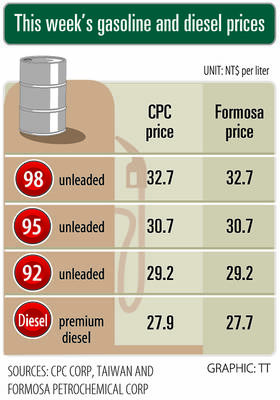

Gasoline and diesel prices this week are to decrease NT$0.5 and NT$1 per liter respectively as international crude prices continued to fall last week, CPC Corp, Taiwan (CPC, 台灣中油) and Formosa Petrochemical Corp (台塑石化) said yesterday. Effective today, gasoline prices at CPC and Formosa stations are to decrease to NT$29.2, NT$30.7 and NT$32.7 per liter for 92, 95 and 98-octane unleaded gasoline respectively, while premium diesel is to cost NT$27.9 per liter at CPC stations and NT$27.7 at Formosa pumps, the companies said in separate statements. Global crude oil prices dropped last week after the eight OPEC+ members said they would