Bigger is better, right?

Not so fast. Corporate America appears to have had second thoughts last year.

Frank Blake, who replaced Robert Nardelli as chief executive of Home Depot, sold off the US$12 billion division that Nardelli set up to serve professional builders.

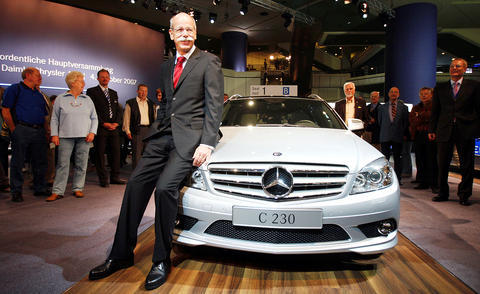

PHOTO: AFP

"Bob's strategy was, `Enhance, extend, expand,' go after adjacent markets and adjacent customers," Blake said. "My vision is that all key investments, be they human resources or money or time, should be focused on the core retail business."

When Fred Poses became chief of American Standard Cos. in 2000, he inherited a company that had steadily branched out from bath and kitchen fixtures into such disparate areas as air conditioning and braking systems for vehicles. Last year, he sold the legacy business, spun off the Wabco braking unit and changed the company's name to Trane, its signature air-conditioning brand. And just last month, he sold Trane to Ingersoll-Rand, which had itself pared down in prior months.

American Standard "had three good businesses that didn't have commonality of customers, of the way they went to market, of materials or manufacturing processes or technology," Poses said. "We realized there just wasn't a lot of value in keeping them together."

Corporate executives and their Wall Street mavens are subject to fads, and they have gone through previous periods in which first broadening and then narrowing business portfolios have taken center stage. At the moment, scaling back appears to be enjoying the upper hand.

Edward Breen, who replaced Leo Dennis Kozlowski as Tyco International's chief in 2002, spun off Tyco's electronics and health care businesses last year, leaving Tyco with its product roster of safety equipment, valves and controls.

DaimlerChrysler is once again Daimler and Chrysler. Many investors speculate that Time Warner may hive off parts of itself.

Many Citigroup investors are clamoring for the company to undo the financial supermarket model that had guided its growth strategy for years.

"There's a huge pressure on chief executives for performance these days," said Joseph Bower, who specializes in management at the Harvard Business School. "So when the corporate office starts looking at its portfolio, it often discovers there are pieces that don't fit."

This is not the first time that company executives have devoted their energies to getting big, only to find that size does not necessarily equal profit.

Throughout the 1960s, companies like ITT and Textron bought up businesses as disparate as hotels, food and machine tools. The prevailing ideas were that a good manager can manage anything, economies of scale would always yield lower costs and a hodgepodge of businesses was the best hedge against economic cycles. Shareholders believed all that, too, and conglomerate shares soared.

Then management consultants and business schools started to promulgate the idea of "core competencies" -- the notion that firmss should focus only on businesses that best fit their skills and distribution channels.

Shareholders hopped on board and began selling conglomerate stocks, prompting many such companies -- General Electric is an exception -- to shed businesses that weren't an obvious fit.

Over the last few years, many companies, scrambling for new ways to increase the scale of their core businesses, broadened their definition of core competency.

DOING IT ALL

Citigroup was in the money business -- so why not sell products to consumers, businesses and investors alike? Home Depot was already selling to small contractors via its stores, so why not serve mega-builders directly?

Kozlowski, who had built Tyco into a "three-legged stool" that rested on fire detectors, medical products and electronic components, added a fourth leg, a financial company, with the idea that offering financing would help the other legs grow.

Now shareholders have grown disaffected with many of these new age conglomerates, too. They again recognize that they can diversify their own portfolios by buying shares of single-focus companies -- or, they can simply invest in mutual funds that are by definition diversified.

"There is a growing sense among investors that portfolio managers do a better job than corporate managers," said Kathryn Rudie Harrigan, a professor of business leadership at the Columbia Business School. "So they are asking point-blank, `Why are you keeping these businesses together?'"

Corporate chiefs are having a harder time answering that question. Many of the perceived synergies between disparate businesses never really panned out, no matter how good they looked on paper.

That is the reasoning behind the growing clamor among Citigroup investors for the financial behemoth to break itself into a consumer bank, an investment bank and a brokerage firm.

"Banks that want to be one-stop shops for financial transactions must realize that it takes more than a pat on the back to get stockbrokers to cross-sell loans," said Robert Gertner, a professor of economics and strategy at the University of Chicago Graduate School of Business.

Disgruntled investors are more vehement. "The whole idea of a financial supermarket is ridiculous," said William Smith, president of SAM Advisors, a money management firm that owns Citigroup shares. "You can't cross-sell, because the investment bankers won't let brokers court their clients, and individuals don't want their personal bankers ramming a mutual fund down their throat."

Citigroup officials do not necessarily disagree.

Gary Crittenden, chief financial officer of Citigroup, said: "Cross-selling is always difficult."

He stressed that he does not know if Vikram Pandit, Citigroup's new chief executive, will dissect the company.

But Crittenden does tick off reasons he thinks the Citigroup structure works. He notes that it provides a flow of capital from mature businesses like domestic credit cards into growing businesses, like the bank Citigroup just bought in Taiwan. And he says that diversified revenue and income streams lead to a much stronger credit rating.

"There are many compelling reasons why the pieces of this company fit well," he said.

Such rationales were heard in the last wave of corporate break-ups too, of course. The element that has been added this time is the rising influence of private equity firms. While many are somewhat cash-squeezed now, in recent years they have formed a steady stream of buyers for the assets the slimming down companies divest.

An alliance of private equity firms paid US$8.5 billion for Home Depot Supply, as the company's professional unit was called. It was less than Home Depot had originally expected, but more than it probably could have gotten from a strategic buyer, considering faltering home-building markets and tight credit.

Bain Capital Partners paid US$1.76 billion for American Standard's bath and kitchen business.

`EXIT STRATEGY'

"Private equity has created an exit strategy for parts of portfolios that are not attractive to strategic buyers," said Poses, the Trane chief.

Moreover, the specter of a deep-pocketed equity firm waiting to pounce can tip management into sloughing off divisions they might otherwise have held.

And private equity firms no longer simply buy up companies, cut costs and flip them back to the public markets. Many private firms now buy along a theme: They snap up assets, roll them up into huge companies -- think Wilbur Ross and his steel, coal and textiles companies -- that they manage for years before they take them public.

"There's been a real migration from the old private equity firm that was managed by the numbers. Today's private equity companies are the new conglomerates," Harrigan said.

If true, they may face some challenges of their own. Management experts, and a growing number of chief executives themselves, are conceding that even the smartest people become distracted if they are pulled in too many directions at once.

The main reason Blake decided to sell Home Depot Supply was that he wanted to tinker with product mixes, expand to new markets and experiment with new store formats. In other words, he wanted to concentrate on the stores.

"It was a question of focus," he said. "Supply would have diverted too much attention and resources that had to go to retail."

The US dollar was trading at NT$29.7 at 10am today on the Taipei Foreign Exchange, as the New Taiwan dollar gained NT$1.364 from the previous close last week. The NT dollar continued to rise today, after surging 3.07 percent on Friday. After opening at NT$30.91, the NT dollar gained more than NT$1 in just 15 minutes, briefly passing the NT$30 mark. Before the US Department of the Treasury's semi-annual currency report came out, expectations that the NT dollar would keep rising were already building. The NT dollar on Friday closed at NT$31.064, up by NT$0.953 — a 3.07 percent single-day gain. Today,

‘SHORT TERM’: The local currency would likely remain strong in the near term, driven by anticipated US trade pressure, capital inflows and expectations of a US Fed rate cut The US dollar is expected to fall below NT$30 in the near term, as traders anticipate increased pressure from Washington for Taiwan to allow the New Taiwan dollar to appreciate, Cathay United Bank (國泰世華銀行) chief economist Lin Chi-chao (林啟超) said. Following a sharp drop in the greenback against the NT dollar on Friday, Lin told the Central News Agency that the local currency is likely to remain strong in the short term, driven in part by market psychology surrounding anticipated US policy pressure. On Friday, the US dollar fell NT$0.953, or 3.07 percent, closing at NT$31.064 — its lowest level since Jan.

The New Taiwan dollar and Taiwanese stocks surged on signs that trade tensions between the world’s top two economies might start easing and as US tech earnings boosted the outlook of the nation’s semiconductor exports. The NT dollar strengthened as much as 3.8 percent versus the US dollar to 30.815, the biggest intraday gain since January 2011, closing at NT$31.064. The benchmark TAIEX jumped 2.73 percent to outperform the region’s equity gauges. Outlook for global trade improved after China said it is assessing possible trade talks with the US, providing a boost for the nation’s currency and shares. As the NT dollar

The Financial Supervisory Commission (FSC) yesterday met with some of the nation’s largest insurance companies as a skyrocketing New Taiwan dollar piles pressure on their hundreds of billions of dollars in US bond investments. The commission has asked some life insurance firms, among the biggest Asian holders of US debt, to discuss how the rapidly strengthening NT dollar has impacted their operations, people familiar with the matter said. The meeting took place as the NT dollar jumped as much as 5 percent yesterday, its biggest intraday gain in more than three decades. The local currency surged as exporters rushed to