Google Inc's share sale has put Wall Street on notice: The old way of doing business may be ending.

The six-year-old Internet startup based in Mountain View, California, dodged US investment banks and auctioned shares directly to investors. The initial public offering's 28 underwriters, led by Credit Suisse First Boston and Morgan Stanley, received half their usual fees because they weren't needed to find buyers.

PHOTO: AP

"It threatens the large profits Wall Street has made over generations," said Sam Hayes, professor emeritus of investment banking at Harvard Business School. IPOs by Dutch auction "will gradually supplant the traditional IPO."

Managing IPOs, among Wall Street's most lucrative assignments, often pays fees 10 times greater than underwriting investment-grade corporate bonds. Bank fees for US IPOs have averaged 5.7 percent so far this year, little changed from where they stood in 1999, data compiled by Bloomberg show. In Europe, banks competing to manage IPOs have cut fees to the lowest level since 1998.

Shares of Google, owner of the world's most-used Internet search engine, jumped 18 percent yesterday in their first day of trading, rising US$15.34 to US$100.34 on the NASDAQ Stock Market.

Google ended its IPO auction the day before, selling 19.6 million shares at US$85 each to raise US$1.67 billion. It was the second-biggest offering by an Internet company after the US$1.9 billion offering by Genuity Inc. in 2000. Genuity filed for bankruptcy in November 2002.

Missteps

A series of missteps by Google executives forced the company to halve the value of the offering, reducing the price from an initial forecast of as much as US$135 and reducing the number of shares offered. Still, the transaction was completed in the face of a flagging market that stifled demand for new stocks. Nineteen US companies have withdrawn or postponed their IPOs this month.

"It was successful," said Mark Herskovitz, who manages US$2.2 billion in technology stocks for Dreyfus Corp in New York. "The amount of money they raised was huge. The stock even at US$85 has a pretty high valuation, so the company made a lot of money." He declined to say if he bought shares.

The sale gave Google a higher market value than Amazon.com Inc, the world's largest online retailer, valued at US$16 billion, or IAC/InterActiveCorp, the world's largest online travel company, valued at US$16.4 billion. Yesterday, Google was one of only 20 companies on the New York Stock Exchange, Nasdaq Stock Market or the American Stock Exchange whose shares traded for more than US$100 each.

Auctions, besides cutting the lucrative banking fees of traditional IPOs, make the process more open and transparent to smaller investors, Google and other backers say.

"If you have an auction, you get supply and demand financing," said John Coffee, a professor of securities law at Columbia University.

"Wall Street doesn't like auctions and wanted this one to fail, but it didn't fail. You will see more auctions."

It may take years for the auction to dominate because few on Wall Street will champion it, said Harvard Business School's Hayes, 69. "It requires 500-pound gorillas to do it: companies, like Google, that can go over the heads of investment bankers directly to investors. It could take a number of years."

Equity underwriting, including IPOs and subsequent stock sales, accounted for more than 35 percent of investment-banking revenue at New York-based Morgan Stanley in the second quarter and more than 20 percent at Goldman, Sachs & Co, also based in New York.

Dutch Auction

Google is the latest -- and largest -- company to defy Wall Street convention by auctioning stock to the public. The so-called Dutch auction process, which Silicon Valley banker William Hambrecht helped pioneer, is designed to include smaller investors often shut out of traditional offerings while helping companies keep more of the sale's proceeds.

In a conventional IPO, underwriters gauge demand for the offering among investment managers and set a price range based on their interest. Only those on investment banks' list of clients and company insiders are invited to buy the shares before they begin trading.

In Google's auction, investors placed bids specifying the price they would be willing to pay for the shares. Google and its underwriters then determined the highest price at which they could sell all the shares offered.

"What an auction system does is opens up the offering to all channels of demand," Hambrecht said in a February interview.

His firm, San Francisco-based WR Hambrecht + Co, has raised US$342.8 million through 10 IPOs using an auction-style system it calls "OpenIPO." Hambrecht, through spokeswoman Sharon Smith, declined to comment for this story.

Hambrecht conducted the first-ever Internet-based auction IPO in Feb. 1999, selling 1 million shares for Ravenswood Winery, raising US$11.6 million.

Dutch auctions have been tried in other markets to lower the cost. As senior vice president for finance at Exxon Corp in the late 1970s, Jack F. Bennett pioneered the use of auctions to sell commercial paper directly to investors.

"That's probably the wave of the future," Bennett, 80, said of selling shares through auctions on the Internet. "The Dutch auction is probably not suitable for a very small company that's not well known. But if you're dealing with a company that everyone knows, like Exxon or Google, it's a natural."

A Typical Misadventure

Google's auction was plagued by missteps. Twice this month, the company told shareholders that it may have run afoul of securities laws. On Aug. 4, Google said it failed to register 23.2 million shares distributed to employees and consultants. Google yesterday said the SEC was investigating whether an interview with Founders Larry Page, 31, and Sergey Brin, 30, in Playboy magazine might have violated disclosure rules.

"It was a typical misadventure," John Gutfreund, senior managing director of New York-based investment bank C.E. Unterberg, Towbin, said of the auction. Google "filed too high a price, partially because of the greed of the owners and partially because of the greed of the underwriters who told them they could get a high price," said Gutfreund, the former chairman of Salomon Brothers Inc.

As a result of the IPO, Page and Brin now hold stakes valued at US$3.28 billion and US$3.27 billion, respectively. Chief Executive Eric Schmidt's 6.1 percent stake is valued at US$1.25 billion.

The 28 underwriters in Google's IPO will earn fees of about US$46.7 million, or 2.8 percent of the sale's total value, Google said in a US Securities and Exchange Commission filing. In contrast, Morgan Stanley collected 4.75 percent in fees from Assurant Inc's February sale of US$2 billion in stock, according to Bloomberg data.

Because banks often price IPO shares below what the market is willing to pay for them, the traditional system rewards favored clients at the expense of companies raising the money, said Patrick Byrne, chief executive of Overstock.com Inc, an online retailer that raised US$39 million through an auction-style IPO in May 2002.

"CEOs and boards that don't use the auction process should have their heads examined," said Byrne, who hired Hambrecht to underwrite Overstock.com's IPO. "If you go to a conventional bank, what they will do is make the market as hot as they can, then allocate stock to their buddies and some greasy hedge fund."

That's the reason as many as six investment banks declined to join Hambrecht in underwriting the Overstock.com IPO, even if they all initially cited other reasons for the rejection, Byrne said. He declined to name the banks.

Friends of Frank

Frank Quattrone, a former CSFB banker, was convicted of obstructing justice in May for hindering federal investigations into how CSFB doled out shares of IPOs. During the trial, Quattrone acknowledged he recommended allocating stock to some banking clients and that he was asked to provide extra IPO shares for a list of clients, the so-called Friends of Frank.

Wall Street figures including Richard Jenrette say Google provided an example not to follow. Jenrette in 1959 co-founded Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette, a securities firm Credit Suisse First Boston bought in 2000.

"The complexities and frustration of the Dutch auction suggest that it's not a good thing," said Jenrette, 75. "The process with Google was agonizingly long and drawn out. Their fees may be too high, but investment bankers strike a balance between the corporations and the investors. The deals get done."

Jenrette said investment bankers have been accused of contradictory misdeeds. During the late 1990s, they allegedly priced computer-related IPOs too low. As shares doubled or tripled on their opening day, favored investors profited at the expense of companies themselves. Later, after many stocks lost 99 percent or more of their value, bankers were accused of having priced shares too high.

"It takes a lot of chutzpah to say they didn't get enough for the companies," he said.

It isn't realistic for individual investors to price stocks in an auction, he said. "To expect unsophisticated people to make a bid -- it's hard to price," he said. "Everything that's old isn't bad."

Auctions aren't for everyone, said Bruce Twickler, founder and chief executive of Andover.net Inc, a software developer that sold shares to the public in a December 1999 auction.

Andover.net's offering raised US$82.8 million, and the stock more than tripled in its first day of trading. Andover.net's focus on programs based on the Linux operating system, which was emerging as a popular alternative to Microsoft Corp's Windows software, gave Twickler access to a pool of would-be investors few companies could tap.

"When you have a very dedicated community, customers, clients -- whatever -- it's something that's more appropriate," said Twickler, who left Andover.net following its 2000 sale to rival VA Software Corp and now makes documentary films.

Marquee Names

The auction process is "only going to work for marquee names," said Michael Madden, former head of investment banking with Kidder Peabody & Co and Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc, now a principal with buyout firm Questor Management. "How are you going to build interest without a selling a concession? I don't think this changes everything."

Companies lacking the Google's cachet with individual investors may stick with banks that use a legion of brokers to drum up demand, he said.

"We believe as a firm that the traditional IPO process, having a distribution network and the capital to support transactions, still matters," said Paul Phillips, the head of technology investment banking at Banc of America Securities LLC.

During the auction, Google refused to provide earnings forecasts, and gave little new information during presentations promoting the offering. Google also said Brin and Page would sell stock in the IPO, unlike most founders, and would hold a special class of stock that gave them 10 votes for every share, compared with one vote for every share being sold in the IPO.

The Google auction is a historic precedent, said Dave Briggs, head of equity trading at Federated Investors Inc, which oversees US$25 billion.

"The genie is out of the bottle," he said. "It's a high-profile event. It will cause people to consider an auction as an option when they might not have thought about it."

Hon Hai Precision Industry Co (鴻海精密) yesterday said that its research institute has launched its first advanced artificial intelligence (AI) large language model (LLM) using traditional Chinese, with technology assistance from Nvidia Corp. Hon Hai, also known as Foxconn Technology Group (富士康科技集團), said the LLM, FoxBrain, is expected to improve its data analysis capabilities for smart manufacturing, and electric vehicle and smart city development. An LLM is a type of AI trained on vast amounts of text data and uses deep learning techniques, particularly neural networks, to process and generate language. They are essential for building and improving AI-powered servers. Nvidia provided assistance

DOMESTIC SUPPLY: The probe comes as Donald Trump has called for the repeal of the US$52.7 billion CHIPS and Science Act, which the US Congress passed in 2022 The Office of the US Trade Representative is to hold a hearing tomorrow into older Chinese-made “legacy” semiconductors that could heap more US tariffs on chips from China that power everyday goods from cars to washing machines to telecoms equipment. The probe, which began during former US president Joe Biden’s tenure in December last year, aims to protect US and other semiconductor producers from China’s massive state-driven buildup of domestic chip supply. A 50 percent US tariff on Chinese semiconductors began on Jan. 1. Legacy chips use older manufacturing processes introduced more than a decade ago and are often far simpler than

STILL HOPEFUL: Delayed payment of NT$5.35 billion from an Indian server client sent its earnings plunging last year, but the firm expects a gradual pickup ahead Asustek Computer Inc (華碩), the world’s No. 5 PC vendor, yesterday reported an 87 percent slump in net profit for last year, dragged by a massive overdue payment from an Indian cloud service provider. The Indian customer has delayed payment totaling NT$5.35 billion (US$162.7 million), Asustek chief financial officer Nick Wu (吳長榮) told an online earnings conference. Asustek shipped servers to India between April and June last year. The customer told Asustek that it is launching multiple fundraising projects and expected to repay the debt in the short term, Wu said. The Indian customer accounted for less than 10 percent to Asustek’s

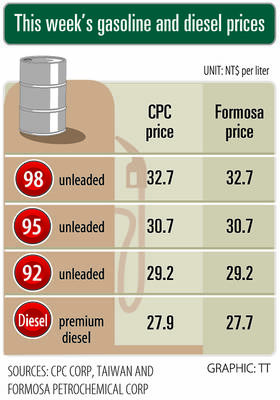

Gasoline and diesel prices this week are to decrease NT$0.5 and NT$1 per liter respectively as international crude prices continued to fall last week, CPC Corp, Taiwan (CPC, 台灣中油) and Formosa Petrochemical Corp (台塑石化) said yesterday. Effective today, gasoline prices at CPC and Formosa stations are to decrease to NT$29.2, NT$30.7 and NT$32.7 per liter for 92, 95 and 98-octane unleaded gasoline respectively, while premium diesel is to cost NT$27.9 per liter at CPC stations and NT$27.7 at Formosa pumps, the companies said in separate statements. Global crude oil prices dropped last week after the eight OPEC+ members said they would